What do research papers say about us?

2019 marked the celebration of 150 glorious years of the periodic table. What it also marked was the 150th anniversary of popular scientific journal Nature.

Getting introduced to literature in what may be a fairly popular setting for a lot of students in India — a rush of other commitments, one too many applications to take care of, or sheer disinterest in spending long hours to find the exact piece of information — can be tumultuous, but can also turn out to be an extremely enriching experience. I never really felt the need to delve into scientific papers until after my third semester in college, and even when I did, I have to admit that I didn’t quite have the temperament to actually grasp every bit of information the paper had to convey (To be noted: I’m not exactly adept at it now, but I’ve certainly improved).

What’s interesting, and not very hard to guess, is that scientific literature wasn’t always the way it is right now. This comprehensive, elaborate version of presenting scientific findings is an elegant improvisation of how people went about sharing ideas and results in the yesteryears. Let me politely scam you into inferring for yourself what insights each of these chronological developments in scientific reporting gives you regarding how humans liked to go about proposing and figuring out stuff about the world.

Rewinding time to the Socratic era, natural philosophers were busy finding “truths” about nature — many of which we can now, thanks to decades of research, pass off as commendable but misguided efforts. However, irrespective of whether their ideas hold true as of today, all of these philosophers worked very hard to come up with questions that boggled minds for a considerable amount of time! Imagine coming up with a question that essentially debases everything that everyone around you believes. And supporting it with your own theory which is branded make-believe by popular opinion. And then being pompous about it. Unsurprisingly, a lot of philosophers didn’t agree with each other. It was, however, agreed upon that there can be only one universal truth, and there was only one way to find out who was right about something — waging war.

Cue exclamatory text. That’s the good stuff!

Cue exclamatory text. That’s the good stuff!

Of course not. The method chosen was debating things out and using substantial proof to support every stance that constituted an argument. The winner takes all (disciples).

Many of these philosophers founded schools of thought — a group of people who subscribed to the same beliefs and ideologies. Their students began writing down things that were said and discussed; often, points made during debates which were befitting medieval equivalents of mic-drops were celebrated, and jotted down for further roasting purposes. This is also what made ancient Greek pedagogies a good starting point in studying the history of science — they documented stuff!

Not much later, the art of documentation was performed with beliefs centered around the saying “Nullius In Verba”, which is Latin for “on the word of no one” or “take nobody’s word for it”. Ironic as it may seem, it propagated a culture of experimenting and repeatedly verifying a set of results so that anyone who chose to replicate the process could witness the same results for themselves.

Now that it’s evident why findings needed to be documented, we can fast forward to the modern era, skipping the middle where there was a lot of drama and banishment surrounding scientific discoveries.

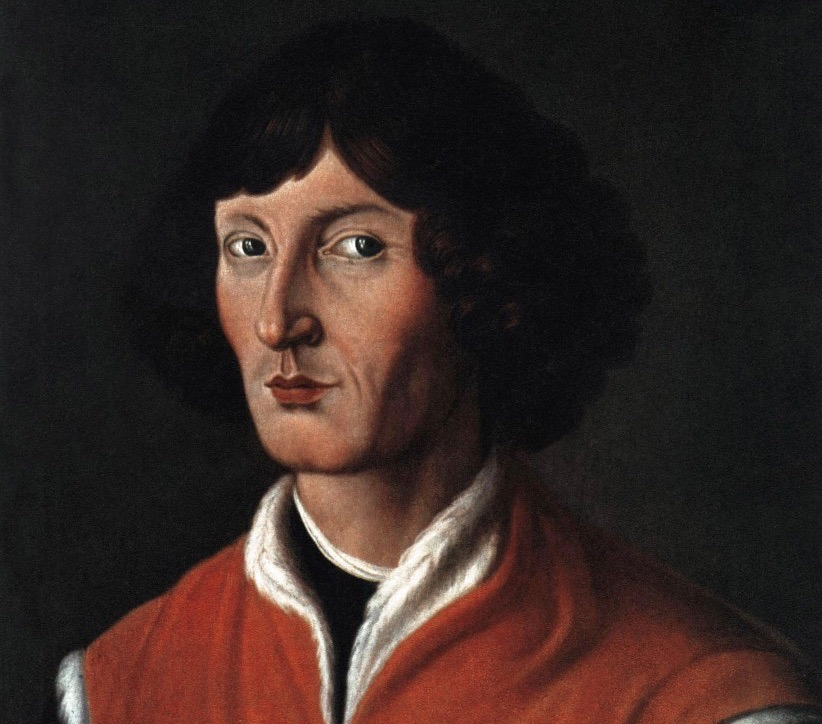

A sullen Copernicus who didn’t feature here.

A sullen Copernicus who didn’t feature here.

It’s the 1600’s. You, a very smart science-person (for the word scientist was coined only much later), can either wait for a fellow researcher’s revolutionary theories to get published in a manner that will make them extremely popular so that they trickle down and find their way to you, or you can keep sending repeated letters to each of these folks, like a scorned lover trying to keep his options open, and hope they write you back, informing you what they’ve been up to so that you may draw all the inspiration you can from ongoing cutting edge research.

Realizing that maybe, just maybe, there might be a method that works faster than writing letters to one another, a small bunch of scientific researchers somewhere in Europe, who like to call themselves the “men of science”, figure they can try and meet up to discuss their ideas and maybe, just maybe, have a little bit of alcohol while at it, too!

And that’s what they did. The first few scholarly societies like the Royal Society (founded in 1660) and the French Academy of Sciences (founded in 1666) started off this way.

Many well-known journals started flourishing in the next couple of centuries and were initially moderated by a small number of marginally drunk editors in a (presumably) European pub, who did a pretty good job of scrutinizing and popularizing the pieces submitted to them.

Saying that these pieces were succinct is probably the understatement of the decade. Watson and Crick’s paper titled “Molecular Structure of Nucleic Acids: A Structure for Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid”, which remains among the most revolutionary and impactful articles to ever be published, is only about 1.5 pages long.

Slowly and steadily, in an effort to avoid reporting any erroneous evidence so as to remain reputable, journals began employing a larger number of people to review the pieces submitted to them. First, a peer review system was put in place, where top tier (which meant highly cited, super popular) scientists having commendable expertise in the said field reviewed the articles submitted to the publication. Later, many successful journals began employing a diverse set of people to jointly review articles along with the peer review system, to strengthen the legitimacy of the piece. The editorial panel saw a rise in the number of women (which was almost always zilch in the 1600’s), as well as the inclusion of scholars from different career stages and other related fields to give inputs on the quality of the article. The approval process that exists today is undoubtedly rigorous, but it also means that the content is reported in a more comprehensible manner, and is definitely in its most accurate form.

Apart from all that you’ve inferred for yourself, this trajectory highlights a trend of moving towards inclusivity and thoroughness. There is an earnest urge to walk away from bad science, and a stringent but fairly wholesome verification process has been put in place to bolster the initiative. I can’t help but view this process to be a simple reflection of the current state of society. And not just now, it has always been society’s reflection as perceived in the mirror of time.

Big thanks to Nature, The Library Quarterly and Scientific American for making the process of digging up information this much fun!