Why you, as a scientifically sound human being, need to care about spectroscopy

Almost every day, new technology disrupts the world and changes the way we interact with it. The word technology invites a lot of attention, and mental mapping makes most of us immediately think about extravagant mobile devices. Of course, if you’re among the more virtuous ones, you’d have thought about the news about Google achieving quantum supremacy or some new concept that is positioned to revolutionize AI.

As students in India, most of us interact with these products or these fields more often than not. (For a variety of reasons. Also, placements. Also, circuital branches. Also, the fact that India is cheap labor and has a sub-par education system in place.)

For no fault of our own — and not that it’s faulty in the first place — any news about a change in the field of pure sciences does not trickle down to us as quickly as the stuff mentioned up there. It’s not all that conspicuous, which makes it seem not all that relevant! Technology, by definition, is “the application of scientific knowledge to the practical aims of human life”. Any applied scientific knowledge counts as tech! In an effort to popularize something very important (and cool) my discipline taught me, I would like to introduce to you, spectroscopy.

Yes, you might’ve attended a lecture or two about it in your freshman year. No, it’s not all number crunching and remembering patterns made of weirdly ordered, and sometimes inverted peaks (which cannot be called ‘troughs’).

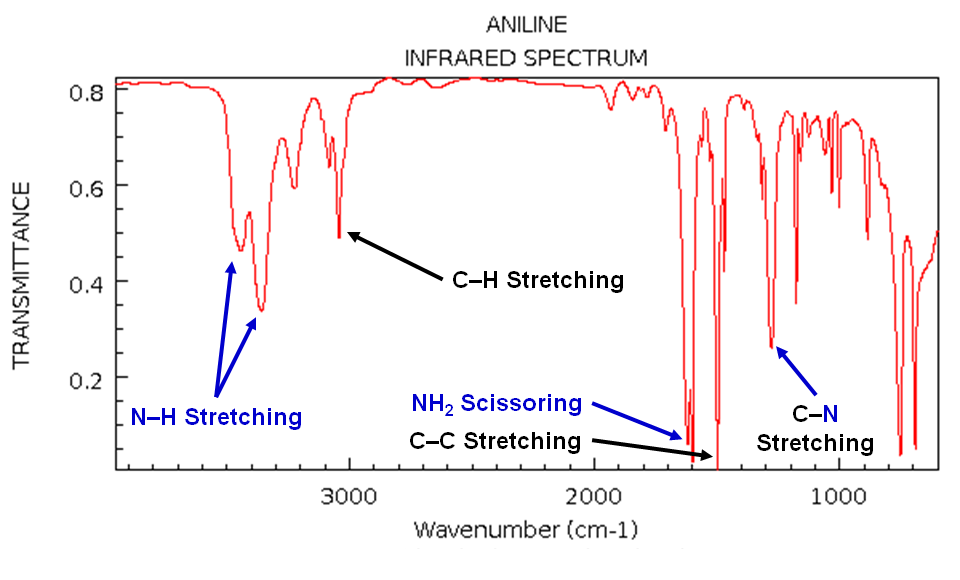

Please stay for the rest of it. This image was not inserted to scare you off.

Please stay for the rest of it. This image was not inserted to scare you off.

Spectroscopy is the study of spectra observed when any kind of matter emits or interacts with electromagnetic radiation.

As and when new methods of understanding the behavior of materials have sprung into existence, we’ve witnessed a surge in the number of inventions that have impacted our lives more remarkably than ever. The nature of materials — which Socrates believed is inevitable to understand in order to do anything at all, and prided himself upon not understanding — is exactly what spectroscopy helps us figure out.

It has enabled us to qualitatively and/or quantitatively describe the nature of a plethora of materials in the form of diagnostic patterns of electromagnetic data.

Now I’m just picking up lines from my BTP report. But there’s no better way to put it!

Each of the numerous spectroscopic methods existing today exploits distinctive fundamental properties of matter to sketch “fingerprints” of materials. Somewhat analogous to a case where a myriad of information from diverse viewpoints (literal, and otherwise) helps paint a more accurate picture of an event, a combination of multiple spectroscopic techniques helps us deduce the properties of a molecule to the best degree possible. All data scientists, take note! It’s easy to gather that spectroscopy generates volumes of data and analysis of the same can be extremely insightful.

What data? Mostly, what and how much energy a molecule absorbs or emits.

Most of us are aware of how energy states of an atom are quantized. We’ve been taught about the different electronic states of an atom. We’ve also been told, that when atoms come close enough and the whole situation is energetically favorable, they can form bonds (essentially, molecules). These can break too. What becomes college-level chemistry is that these bonds can bend, vibrate, gyrate — all that kind of hocus pocus — when they interact with incoming energy. When we fix this energy source in a way that we know exactly how much energy we’re sending in and record what our molecule does with it, we become legends. Kidding, we basically start interrogating the molecule and wait for it to give up some information about itself. There are different kinds of information this molecule can leak, depending upon what exactly it is.

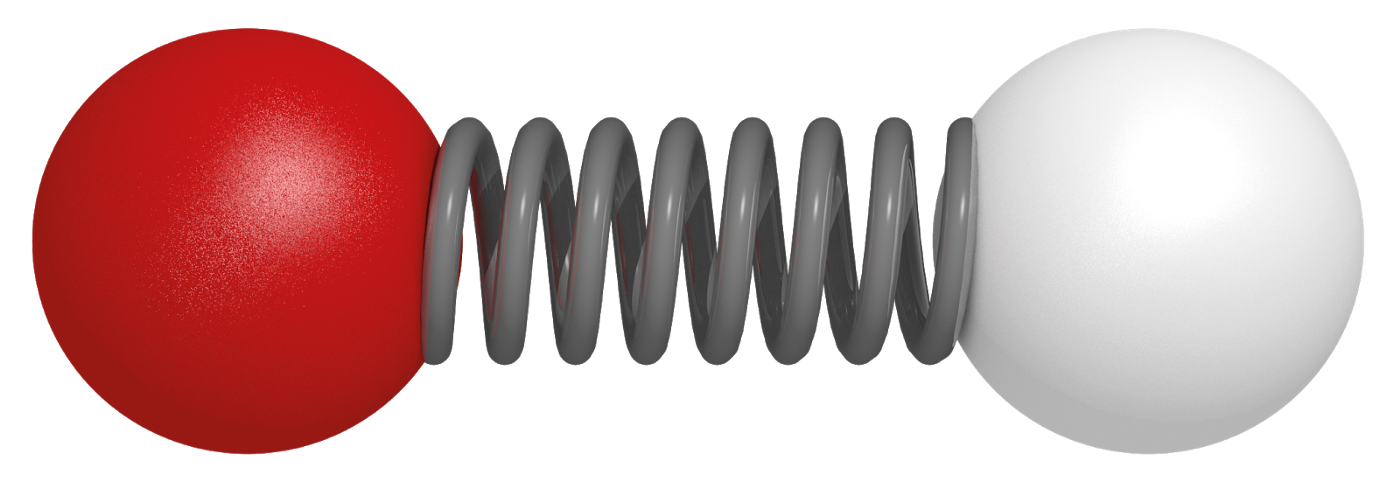

A bond can be thought of as a spring with masses on either side.

This spring can rotate about a point, stretch or contract, and do both of these things at the same time. This hyperactive behavior causes each electronic state to (and I’m not entirely sure if it’s the right way to express it) split into multiple (but quantized) vibrational states, and each of these into rotational states.

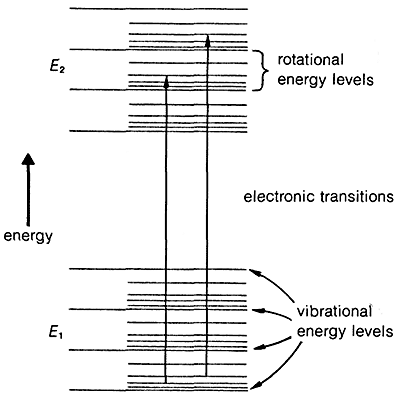

By the end of it, the distribution of energy states looks like this:

The bigger amount of space you see between two states, the more amount of energy you need to gain, or lose, to get from one state to the other! When an electronic excitation/de-excitation occurs, the energy involved belongs to the ultraviolet/visible range of the electromagnetic spectrum. When a vibrational or rotational excitation takes place, a smaller amount of energy is required, normally belonging to the infra-red and microwave ranges.

Each molecule has its own “fingerprint” — a specific behavior when a photon with a specific amount of energy interacts with it — and boom, now you know what UV-visible spectroscopy, microwave spectroscopy, and IR spectroscopy are.

There are other techniques like nuclear magnetic resonance and electron spin resonance, that exploit the orientation of the dipoles (magnetic and electric) associated with the spin of an electron in a molecule to extract information about it. Raman spectroscopy involves exploiting the changing polarisability of a molecule and measuring how much of the incident light is scattered by the molecule. Improvements are being made as you read this!

The data crunching that follows spectroscopic analysis

The data crunching that follows spectroscopic analysis

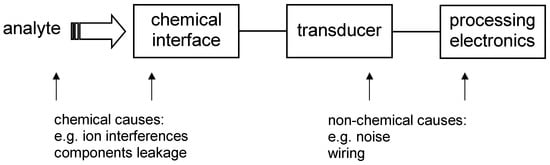

Coming to how all of this matters; everything, quite literally every tangible thing around us is made by understanding the nature of, well, stuff! It’s easy to see how spectroscopy is the first step to go about finding evidence about the behavior of compounds. In astronomy, spectral studies led to the finding that the universe is expanding rapidly and isotropically — a conclusion arrived at after (okay maybe not right after, but you get it) noticing Doppler shifts in the spectra. A lot of these techniques are also being applied in more terrestrial settings, as for example, environmental and biological analysis — basically, the identification of what exactly makes up a pollutant, or a toxin. Detection of toxins (and a lot of other stuff) in trace amounts is being made possible by tweaking spectroscopic environments to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio of the toxin’s recorded “fingerprint”.

I haven’t done enough justice to this bit because of how widespread, but also repetitive, the applications are. The broader point however, is that spectroscopy is the kindergarten to the many schools of science that a college kid joins eventually.

I sincerely, dearly hope you found this interesting. I also sincerely, dearly hope this helps you get your head around a lot of our BTP’s, and in general, a little more interested in the super cool stuff happening in and around the department of chemistry.

Thanks for making it all the way here, didn’t think you would! (This is getting old.)