A 101 to the God particle

Articles written by sophomores seldom make history, and for good reason. – Urban Legend

For some reason, The Startup decided to publish this piece when I put it up on Medium a year later.

The Higgs boson is the origin of all mass. Right?

Whether or not you have an opinion on this, you surely do have one on the number of fundamental particles that exist. Right?

Electrons and protons and neutrons. They make up any and every atom that exists. Right?

Oh but there’s the photon; completely forgot to account for light. That’s four. We have a consensus - a bunch of four particles that make our universe. Right?

Definitely heard of quarks. There’s an up quark and a down quark. And heard of neutrinos. Okay, these exist for sure. Guess that’s right.

In a nutshell, scientists have discovered twelve particles which they choose to call fundamental at this point (circa 2018). The Higgs boson excluded.

Like the periodic table of elements — where a bunch of elements behaves in one way, another bunch behaves in another way — there exists a group of things that scientists at CERN call the periodic table of fundamental particles.

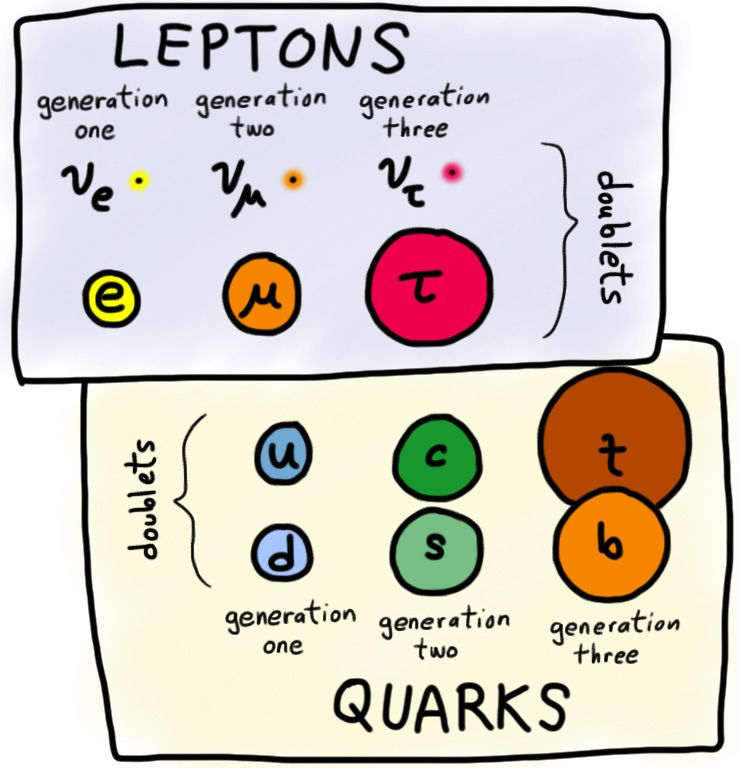

The up-down, charm-strange and top-bottom quarks interact with each other in these very pairs, and the pairs are called doublets. These six particles are called quarks, which became evident by the end of the last sentence.

The electron, muon and the tauon are the leptons. The neutrino-namesakes of these three particles pair up with the three respectively to make lepton doublets. Also, the particles on the right-hand side of any particle have more mass than the particle itself. So we have a charge versus mass table, in some sense.

The first fundamental particle to be discovered was a lepton — the electron, and wasn’t really classified as a ‘lepton’ back then. In fact, it wasn’t really classified as anything. With time, and the discovery of the proton and neutron, a classification developed. The eventual subatomic findings using the Large Hadron Collider have gotten us knowledge of the quarks and the new leptons. In the Large Hadron Collider, two subatomic particles traveling at really really high speeds (just shy of the speed of light!) are made to collide and are thus, annihilated. The interesting thing is that what comes from the annihilation does not specifically have to be a re-arrangement of what went in.

So what is this fuss about the Higgs boson anyway?

The Higgs boson is the quantum excitation of the Higgs field, one of the particles that scientists predicted would come from the series of annihilations.

And the Higgs field is?

A result of the Higgs theory, which was a result of the question, ‘where does mass come from?’ The Higgs theory starts with this :

This field treats mass as a kind of charge. Gravitational charge, let’s say. The particles that interact more strongly with this field are slowed down — inertia might be the analogy to the interaction — and are said to have mass.

Particles that aren’t affected by this field — like say, the photon — are called massless. Think of a ping-pong ball submerged in water. When you push the ping-pong ball, it will feel much more massive than it does outside of water. Its interaction with the water has the effect of endowing it with ‘extra’ mass. So is with particles submerged in the Higgs field versus empty space.

The theory further says that the Higgs boson is the particle responsible for ‘giving’ mass to other particles. It represents a new form of matter, which had been widely anticipated for decades but had never been seen. In the early 20th century, physicists realized that particles, in addition to their mass and electric charge, have a third defining feature: their spin. But unlike a spinning top toy, a particle’s spin is an intrinsic feature that doesn’t change, it doesn’t speed up or slow down over time. Electrons and quarks have the same spin value, while the spin of photons is twice that of electrons and quarks. The equations describing the Higgs particle showed that unlike any other fundamental particle species, it should have no spin at all. Data from the Large Hadron Collider have now confirmed this.

Finding the Higgs boson basically meant that we now had evidence for the Higgs field. The heart of the matter is this: Without the existence of the Higgs, the universe wouldn’t be able to form atoms and molecules. Instead, electrons and quarks would simply flash by at the speed of light, like photons. They’d never be able to form any sort of composite matter. So the universe would be massless. We wouldn’t exist, and neither would anything in any form we recognize.

Understanding that the formation of the boson requires a certain amount of energy, CERN is trying to find practical applications of it in important reactions.

You’re actually pretty free to discover for yourself if there are more ‘fundamental’ particles that are waiting to be found, if quarks can be broken down further, how one can ‘use’ the Higgs particle to make everyday life simpler, and whatnot. Going ahead?